This week the Herald reported the settlement of an important case concerning what happens to our loved ones if they lose capacity to make decisions regarding their own affairs.

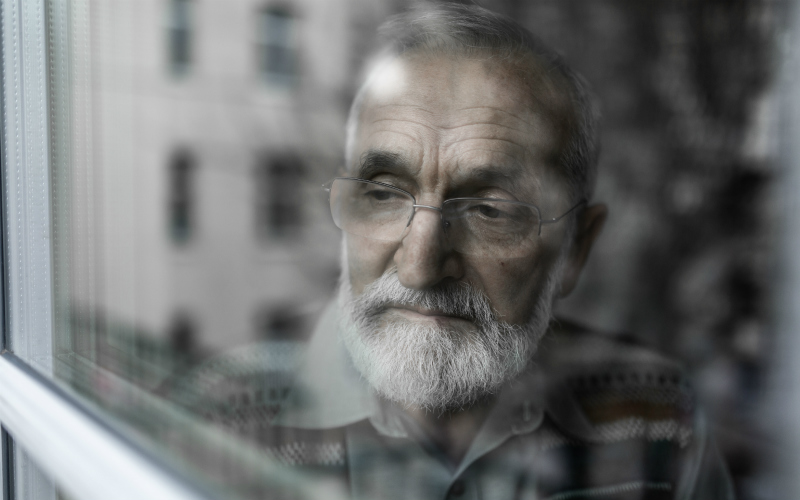

The case arose from a challenge by the Equality and Human Rights Commission to an alleged practice of Glasgow Health and Social Care partnership which saw elderly patients who had been diagnosed with dementia, or other conditions affecting their ability to make informed decisions about their own welfare, being moved from hospital into locked care homes without the legal authority to do so.

The court action called before Lady Carmichael in the Court of Session where parties confirmed that they had reached an agreement that the practice would be discontinued and that a revised patient pathway which “will safeguard the rights of elderly and disabled people” had been devised.

It is encouraging to see the Health Board and the Commission reach a consensus here in a matter which highlights the importance of following the appropriate legal process when it comes to obtaining the right to make decisions on behalf of someone who is unfortunately unable to make those decisions on their own especially where those decisions involve a deprivation of liberty.

Guardianship

The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 sets out the legal process that must be followed to obtain legal guardianship over a relative or loved one who has lost capacity to make decisions relative to their own welfare or finances and who has not previously signed a Power of Attorney.

An application must be lodged with the court asking for only those specific powers which are required, the merits of which will be judged on a case by case basis. The proposed guardians will normally be close relatives of the person who has lost capacity and will be the person or persons who are best place to know their current and past wishes. The Office of the Public Guardian for Scotland must have input into any application made in Scotland, and other relevant family members must be informed of the application and given the opportunity to oppose it if they have reason to believe that the appointment isn’t necessary or suitable. The adult who is affected by the application must also be informed.

Where powers to make welfare decisions are required, such as in relation to care and accommodation and medical treatment, the local authority in which the affected adult lives must appoint a Mental Health Officer to provide a report on the need for the powers sought and the suitability of the proposed guardians. Additionally, two medical reports must be obtained. Proposed guardians will also be required to declare if they have any relevant criminal convictions or if they have ever been barred from working with vulnerable adults.

In cases where financial powers are sought, the proposed guardians will be asked to declare relevant financial history and, after appointment, will require to provide an annual return to the Office of the Public Guardian containing details of how the adult’s finances have been managed. In certain cases, the court will require a form of insurance bond, known as caution (pronounced cay-shun), to be lodged to protect against potential financial mismanagement.

This process is onerous and rightly so. Asking a court to award a person the power to make decisions on where another person lives, who they see, any medical treatment they receive, or how to manage their finances is a very serious responsibility. This legal challenge demonstrates just how significant those decisions are and shows how vital it is that anyone who seeks to make those decisions has the legal authority to do so.

If you need advice or assistance with obtaining a guardianship order for a family member loved one, please contact Sarah Cooper on 03330 430150.